To say I had a sweet tooth as a child would be an understatement. I remember one Easter, I must have eaten over 40 Cadbury Creme Eggs in one sitting. My mom would put a chocolate centerpiece on the table, usually a bunny or an egg or something like that, and it would be surrounded with smaller treats, such as Creme Eggs. What ensued was a complex calculation of how many eggs I could eat before it would look like I ate them all. I had to factor in the fact that my brothers and sister would also eat some eggs, albeit at a slower rate. And I also had to squish all the little foil wrappers in the tiniest, most compact ball possible to make it look like I didn’t actually have that many. Those were the good days.

To say I had a sweet tooth as a child would be an understatement. I remember one Easter, I must have eaten over 40 Cadbury Creme Eggs in one sitting. My mom would put a chocolate centerpiece on the table, usually a bunny or an egg or something like that, and it would be surrounded with smaller treats, such as Creme Eggs. What ensued was a complex calculation of how many eggs I could eat before it would look like I ate them all. I had to factor in the fact that my brothers and sister would also eat some eggs, albeit at a slower rate. And I also had to squish all the little foil wrappers in the tiniest, most compact ball possible to make it look like I didn’t actually have that many. Those were the good days.It’s no secret that children have a more pronounced preference for high-intensity sweetness. This preference may have evolved to make sure children seek out energy-rich nutrition during growth. Therefore, having a child with a sweet tooth was never really a cause for worry. Until now.

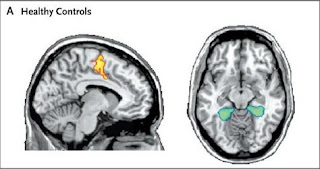

A recent study in the journal Addiction looks at the link between children with a sweet tooth and two other parameters: family history of alcoholism and depression. The researchers picked those two parameters because the pleasure derived from eating something sweet is generated by a reward system in your brain, and both alcoholism and depression affect this reward circuitry. The researchers looked at 300 healthy children, assessed their family history of alcoholism (via an interview with the mother), and tested them for depressive symptoms. They then tested the children for sweetness preference by having them taste sucrose solutions of different sucrose concentrations and asking them to choose which is their favorite. They also assessed the children’s liking for sweet treats in daily life.

The researchers found that almost half of the children were positive for family history of alcoholism, and one quarter of the children exhibited depressive symptoms, consistent with previous studies. When the researchers analyzed sweet preferences, it got messy. First, children with a family history of alcoholism preferred significantly higher sucrose concentrations compared with children with no such family history. Interesting, right? However, if from the total pool of children with a family history of alcoholism, you remove those who also show depressive symptoms, the alcoholism/sweet tooth link is no longer significant. Like I said, messy. Second, children who tested positive for depressive symptoms preferred significantly sweeter foods compared with children who didn’t exhibit depressive symptoms. Interesting, right? However, if you factor in the age of the children, this depression/sweet tooth link is no longer significant (this is because the intensity of the sweet tooth decreases with age). Guess what I’m about to say? That’s right, messy.

Overall, we can draw two conclusions. First, children with a family history of alcoholism AND exhibiting depressive symptoms prefer significantly sweeter solutions. Second, children exhibiting depressive symptoms MAY have a “sweeter tooth” compared with children who don’t exhibit depressive symptoms. Several theories, or a combination of these theories, could explain the associations observed in the study. First, if you read the fine print in the article, you’ll find that the mothers of children who have a family history of alcoholism and depressive symptoms are more likely to be obese. Perhaps these children are exposed to more sweets from an early age? Second, other studies have shown that adults with depression have a higher threshold for the detection of sweet taste. Therefore, it is possible that these children are less sensitive to sucrose and need a higher concentration of sugar to achieve the same level of sweet taste. Third, it is possible that the children with a family history of alcoholism and depressive symptoms have an altered brain reward system and require a higher concentration of sugar to activate the pleasure centers in the brain.

While this study suggests interesting associations, one thing is for sure, more experiments are needed to determine if having a sweet tooth means anything at all. Now excuse me while I unwrap the first Cadbury Creme Egg of the season.

Reference: Sweet preferences and analgesia during childhood: effects of family history of alcoholism and depression. (2010) Mennella JA, Yanina Pepino M, Lehmann-Castor SM, Yourshaw LM. Addiction. Feb 9 [Epub ahead of print].