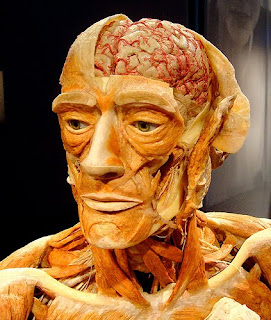

The traveling exhibit Body Worlds & the Brain has arrived in Vancouver. For those of you who are not familiar with Body Worlds, it is an exhibit that features real human bodies and human body parts that have been preserved through a process called plastination. Through my new line of work at the National Core for Neuroethics, I've become involved with Science World, the organization hosting the exhibit in Vancouver. And because of this involvement, I have now seen the exhibit for the first time. Here are my thoughts about Body Worlds, and I would be most interested to hear yours, whether you've seen it or not.

The traveling exhibit Body Worlds & the Brain has arrived in Vancouver. For those of you who are not familiar with Body Worlds, it is an exhibit that features real human bodies and human body parts that have been preserved through a process called plastination. Through my new line of work at the National Core for Neuroethics, I've become involved with Science World, the organization hosting the exhibit in Vancouver. And because of this involvement, I have now seen the exhibit for the first time. Here are my thoughts about Body Worlds, and I would be most interested to hear yours, whether you've seen it or not.Before seeing the exhibit, I wasn't very warm at the idea. I had read a lot of ethics articles questioning whether the exhibit preserved human dignity, and whether human bodies could be considered art. The thought of those preserved bodies, with their eyes staring at me, definitely gave me the creeps. I was concerned with issues like consent, and I was uneasy with the fact that the whole thing felt like a freak show, a very profitable freak show.

I was lucky to see the exhibit on a special opening night for volunteers. On the plus side, it wasn't very busy, and I got to scrutinize everything. On the down side, this meant I had to listen to endless speeches before entering the exhibit.

It's during one of these speeches that my gut feeling about Body Worlds completely turned around (keep in mind, by then I still haven't seen any part of the actual exhibit). One of the speakers discussed how powerful it is to witness the complexity and fragility of the human body, and how this can lead to profound changes in how we view ourselves, and how we take care of ourselves. The speaker was very convincing. Seeing as I'm concerned with caring for my body and tremendously interested in science communication, I started thinking that perhaps I was wrong, and perhaps the "good" of the exhibit (teaching people about the fragility of their bodies) far outweighed the "bad" (ethical questions about dignity and such).

Then I finally got to enter the exhibit and decide for myself, and a really funny thing happened: nothing. I didn't feel any strong negative emotions, didn't think it was gross, inappropriate, or disturbing. But I also didn't feel any strong positive emotions either: didn't think it was cool, beautiful, or awe-inspiring. I mostly didn't care, and frankly I was quite bored by the end of it all.

I'm not quite sure what to make of this as I was very much expecting to feel something. Part of the reason for my lack of interest could have been that the shock factor was lost on me. After several years of dissecting rodents, I've seen my fair share of guts and brains, albeit on a smaller scale. Perhaps I had over-thought the whole thing too much prior to seeing it. I'm not sure.

I would love to read your thoughts about this. Have you heard of Body Worlds? Were you motivated to go see it? What was your gut instinct if you did see it? What did you learn? If you chose not to see it, why? Share in the comments!